|

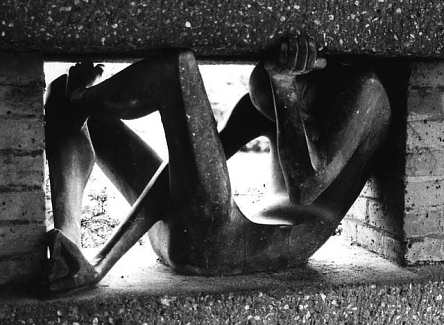

1st september 2003Searching for an old bookseller friend's whereabouts online, I found this excellent sculpture, set into the walls of a block of flats in southeast London:

I'm not sure which of the two subjects the figure represents, though.

4th september 2003Was it Van Gogh who said that he was aware of the sun even at night, as it travelled around the other side of the planet? I was hoping to quote him here as a prefix to the following Jefferies passage, but I can't find the reference. Maybe someone can help. The sward on the path on which Bevis used to lie and gaze up in the summer evening, was real, and tangible; the earth under was real; and so too the elms, the oak, the ash trees, were real and tangible - things to be touched and known to be. Now like these, the mind, stepping from the one to the other, knew and almost felt the stars to be real and not mere specks of light, but things that were there by day over the elms as well as by night, and not apparitions of the evening departing at the twittering of the swallows. They were real, and the touch of his mind felt to them.

He could not, as he reclined on the garden path by the strawberries, physically reach to and feel the oak; but he could feel the oak in his mind, and so from the oak, stepping beyond it, he felt the stars. They were always there by day as well as by night. The Bear did not sink, the sun in summer only dipped, and his reflection - the travelling dawn - shone above him, and so from these unravelling out the enlarging sky, he felt as well as knew that neither the stars nor the sun ever rose or set. The heavens were always around and with him. The strawberries and the sward of the garden path, he himself reclining there, were moving through, among, and between the stars; they were as much by him as the strawberry leaves. By day the sun, as he sat down under the oak, was as much by him as the boughs of the great tree. It was by him like the swallows. The heavens were as much a part of life as the elms, the oak, the house, the garden and orchard, the meadow and the brook. They were no more separated than the furniture of the parlour, than the old oak chair where he sat, and saw the new moon shine over the mulberry-tree. They were neither above nor beneath, they were in the same place with him; just as when you walk in a wood the trees are all about you, on a plane with you, so he felt the constellations and the sun on a plane with him, and that he was moving among them as the earth rolled on, like them, with them, in the stream of space. The day did not shut off the stars, the night did not shut off the sun; they were always there. Not that he always thought of them, but they were never dismissed. When he listened to the green-finches sweetly calling in the hawthorn, or when he read his books, poring over the Odyssey, with the sunshine on the wall, they were always there; there was no severance. Bevis lived not only out to the finches and the swallows, to the far-away hills, but he lived out and felt out to the sky. It was living, not thinking. He lived it, never thinking, as the finches live their sunny life in the happy days of June. There was magic in everything, blades of grass and stars, the sun and the stones upon the ground. The green path by the strawberries was the centre of the world, and round about it by day and night the sun circled in a magical golden ring. from Richard Jefferies, Bevis

9th september 2003The chicken used to be a dinosaur - but that doesn't stop us eating him every day. An old woman is like a fish: one drowns in water, the other in air. When wolves learn to fly, the season for sleeping on the roof is over. The crab thinks himself a fine fellow, but of boiling water he knows nothing. If a man dreams of money, he probably has none. But if he dreams of flames, it may be that his bed is on fire. Whether it's a lamb or a porcupine that has fallen down the well, the water is spoilt just the same. Adam and Eve asked of God: give us food, a bed, and make us laugh. God gave them a duck. The ox is patient, so patient. He knows that in the end his time will come.

10th september 2003"When I wake up I will be on dusty earth, in a city with a past, eating food with spices."

11th september 2003Reading Melville's Typee, I suddenly realise, this is where Wells' The Time Machine came from.

12th september 2003While looking up current thinking on quasars (a bit vague, but moving towards the idea of young galaxies going through an intense period of matter being sucked into a central black hole) I thought of my brief but enlightening summer job in the University of Cambridge (UK) Dept of Astronomy.

19th september 2003Crows, or a crow, had been at the windlass again. Sometime between dawn and the people in the house waking up, they'd messed with the rope and pushed the bucket down the well. The rope was now a horrible tangle around the wooden shaft, and the bucket, it turned out, was jammed between the corners of two stones near the well bottom. Thanks, pal.

24th september 2003Listening to a book read on the radio, on one of the first celebrity chefs, Antonin Careme, who floreated in post-revolutionary Paris. Pre the revolution, restaurants served only soup, which was thought to have restorative medical qualities, to those who could afford it. In the new democratic age they became more generalized eating houses, and chefs rose from their kitchens to become cooks to the stars, or at least to royalty.

25th september 2003No Hiding PlaceThursday, 25 September 2003 This is No Hiding Place, © Thursday, 25 September 2003. It is a sequel to The Eternal is Thy Refuge, and is part of bhikku.net.

|

|